The Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) invests in two ‘traditional’ enterprise challenge funds – the A$17 million DFAT funded Tetra Tech-managed Enterprise Challenge Fund for the Pacific and South East Asia (ECF) and the US$200 million multi-donor funded Africa Enterprise Challenge Fund (AECF).

Challenge funds provide public money into competitions where the private sector develops an innovative approach or scales proven innovations, as well as leveraging investment from large corporates, into initiatives that yield social benefits. The public money will fund up to 50% of the project costs – to a cap outlined in the fund’s eligibility criteria.

These funding mechanisms are the subject of much debate. Is it good aid to give grants to the private sector? Do private sector companies use grants to fund something they couldn’t afford to fund elsewise? Is this a good use of public money when instead we can invest in schools or vaccinations?

Challenge funds come in all different shapes and sizes. In looking at the outcomes to date for both the DFAT funded challenge funds, where Tetra Tech has had the chance to work alongside the team’s implementing the fund – it is clear there are a lot of differences but also a lot of similarities.

Key differences

Firstly the two challenge funds are of completely different scale.

- The ECF was funded with a modest budget of AUD $17million for grants and management fees. The ECF funded 22 projects across nine countries in the South East Asia and the Pacific with mostly medium sized enterprises and a small number of larger businesses. The ECF companies invested AUD $17.8 million or a leverage ratio of 1.62 : 1

- The AECF reaches across Africa with projects operating now in more than 30 countries and has funded close to 200 projects working with a mix of companies including large multi-national corporations. Since 2008, the fund has grown to more than US$200 million with funding from a number of donors. This growth has catalysed in the past two years with an extraordinary increase in the number of projects funded requiring significant changes to management of the fund. The AECF has private sector investment in excess of 3:1.

In challenge funds, particular donor priorities, either sectors or countries can be targeted through either limiting the fund’s eligibility criteria or through operating windows – specific competitions for particular countries or sectors.

- The ECF was funded without a specific sector focus and therefore funded projects in varying sectors including agriculture, tourism, renewable energy and finance.

- In contrast, the AECF has focused on eligible sectors – agriculture, agribusiness, renewable energy, adaptation to climate change and access to information and financial services. The AECF has also opened specific windows for particular countries (mostly on donor priorities) including the post conflict window, South Sudan window, Zimbabwe window and Tanzania window.

This has additional benefits – with greater focus in one sector or country, the management is able to work with economies of scale and can better monitor and link projects to each other.

- The ECF had nine country offices and eventually moved to a more regional management structure, as some countries only had one or two funded projects.

- The AECF work out of regional hubs and often have dedicated monitoring staff for countries where a majority of projects have been funded (Kenya, Tanzania and Zimbabwe). These staff are able to create links between funded projects and share lessons as part of the monitoring process. Projects operating over a region have also been funded and some companies have successful expanded their approach to other countries under the fund.

This was a challenge for the Enterprise Challenge Fund working in the smaller island economies of the Pacific. The limited number of large scale enterprises and low potential for competition within one country made it difficult for ideas to be copied. Again where there were opportunities for projects to be replicated across a number of countries – replication is often done by demonstration – physically seeing success was difficult between islands. However in Africa, AECF has demonstrated that successful ideas can cross country boundaries.

Key similarities

A challenge fund challenges the private sector to propose a project that will benefit the poor and cannot be funded by other means – such as through other donor programs or through traditional finance. This results in often risky but also innovative projects as seen in both funds.

- The AECF funded Mediae company to create three series of a program called Shamba Shape Up that travels to local farms (called shambas in Kiswahili) in Kenya and provides advice on improving the health and function of the farm. The program is in both English and Swahili and is a reality TV show that has a large audience following. The program is now in its fourth series¹.

- The ECF funded Carnival Cruises to develop infrastructure and linkages between cruise passengers and tourist providers from rural areas of Vanuatu. It was the first time a donor had partnered with a cruise ship organisation and this led to a new way of thinking for both Carnival and the Aid Agency. This relationship has endured – with the Minister for Foreign Affairs announcing in November 2013 a continued partnership between DFAT and Carnival.

Challenge funds are expected to have broader impacts on the market – it’s not just about funding one company. These projects are expected to have an impact on other firms in the market.

The more innovative a project is – if it is successful, the more likely it is for others to copy or for other poor people to join in and benefit.

- The ECF funded the WING mobile phone payment system in Cambodia. Many Cambodians lived in areas with no access to formal banking. Sending money to relatives meant physically putting cash into a taxi and sending this across town. WING was a concept developed by the ANZ bank – a cash-in, cash-out and funds payment system through mobile phones. Today WING is the market leader for digital finance in Cambodia. With 1,800 agents and over 1 million users (half of whom are unregistered), WING provides an easy way for all segments of the population to make payments.

- Paperhole established Agri-Hubs—a wholesale market for rural traders as well as a purchasing point for a wide range of commodities. During 2011, about 114 agro-dealers were contracted to stock inputs in 10 Zimbabwean districts, providing 160,000 rural households with access to inputs and a point of sale and creating 14 full-time and 456 part-time jobs².

In addition to others replicating projects, challenge funds can also help prove the investment case for commercial banks and private investors. Challenge fund management often work with traditional financing institutions to talk about opportunities for investment and scaling up.

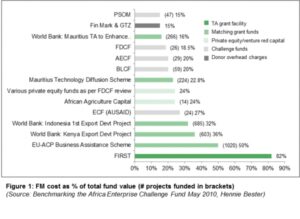

The Fund Manager is the manager and facilitator for a challenge fund. Traditionally challenge funds were funded with a low cost approach to management – a hands-off approach – providing very small amount of funding to oversight, monitoring or evaluation. This led to a deficit of information about if challenge funds actually work and fuels further debate.

- ECF management costs at inception were 27% of the total program costs

- AECF management costs at inception were 20% of total program costs

Both the AECF and ECF have worked with donors to advocate for the improved rigour of monitoring and have investigated results measurement systems in line with the Donor Committee on Enterprise Development (DCED) Standard for Result Measurement. The Standard establishes a reasonable minimum approach to what should be measured and tools for how to do this.

Additionally donors are looking at approaches for evaluation of challenge funds investing in independent monitoring and specific evaluation of market approaches.

- ECF had an Independent Monitoring Team who performed annual independent reviews and performance assessments of the Fund Manager.

- AECF is also setting up an Evaluation Management Unit to undertake similar independent evaluations of the program and funded projects.

So far from being a tale of two challenge funds, there are similarities and also differences in both challenge funds. This is why it has been helpful for Tetra Tech to be involved in both funds (firstly as an implementer and secondly through a consultancy) to enable sharing of lessons between the two programs.

To find out more about Tetra Tech’s challenge fund work visit http://www.enterprisechallengefund.org/