A Theory of Action is the delivery model for a Theory of Change.

Typically, a Theory of Action describes how a project or a program is designed and set up. It articulates the mechanisms through which the activities are being delivered, e.g. through which actors (for example, NGOs, government or markets) and following which processes (for example, grants to NGOs disbursed from a challenge fund, provision of technical assistance, advocacy activities, or the establishment of partnerships).

It is important to articulate a Theory of Action at a program’s design stage because it affects the Theory of Change and the program’s delivery. A program theory simply does not “exist” without a Theory of Action, and its rationale cannot be tested unless the program logic specifies how the ‘change logic’ is going to be implemented.

It is crucial to articulate the Theory of Action for a program from an evaluation perspective. If a Theory of Action is clearly articulated, the evaluator can more easily assess what went wrong – the project or program theory (Theory of Change) or its delivery (Theory of Action).

Tetra Tech International Development both implements and evaluates programs on behalf of clients. Theories of Change have become a standard tool for identifying how a program will lead to the desired outcomes. However, to better understand how to best implement a program, we need to also use Theories of Action. This is important for our evaluation work as well. If a Theory of Action is clearly articulated, the evaluator can more easily assess what went right (or wrong) – the program’s theory or its delivery.

A Theory of Action is the operationalisation of the Theory of Change of a specific program or intervention

While Theories of Change are nowadays commonly found as part of the documentation of a program and their use is increasingly routinised by implementers and evaluators, Theories of Action (or implementation theories) have not been used as often to describe the operationalisation of a program’s activities.

But if Theories of Change are useful for articulating an intervention logic within the complex environment in which programs are being implemented, aren’t implementation theories equally necessary as they are the supporting structure for change?

In this policy brief, we argue that Theories of Change and Theories of Action should be approached as a single exercise at the project design stage.

A Theory of Action illustrates how a program is constructed to ‘activate’ the Theory of Change.

Typically, a Theory of Action describes how a program is designed and set up. To operationalise a program’s Theory of Change, a practitioner should ask:

- Is the program working through partnerships?

- Is the program directly transferring goods and services to beneficiaries?

- Is it a technical assistance program?

- Is it an advocacy program?

For example, a program aiming to increase girls’ school attendance, which is set up as a fund disbursing grants to civil society organisations, is a good example of a program directly transferring goods and services to beneficiaries through civil society.

A program aiming to increase research outputs and knowledge production between the UK higher education sector and partner countries’ universities, policy institutes and research agencies by facilitating the conditions for collaboration is a good example of a delivery model focused on establishing partnerships and long-term linkages between institutions.

Theory of Change and Theory of Action combined provide the program theory.

A Theory of Action is the delivery model for a Theory of Change. A Theory of Change describes the processes through which change comes about for individuals, groups or communities. A Theory of Action articulates the mechanisms through which the activities are being delivered, e.g. through which type of actors (for example, NGOs, government or markets) and following what kind of processes (for example, grants to NGOs disbursed from a challenge fund, provision of technical assistance, advocacy activities, facilitation of or the establishment of partnerships).

It is possible to operationalise the same Theory of Change in different ways, that is, through different Theories of Action.

Theory of Action vs. Theory of Change

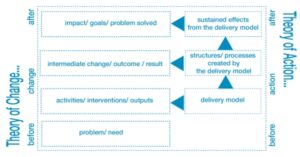

A Theory of Change and a Theory of Action follow the same logical structure: sequential, with steps leading to the long-term goal and objectives of a program.

When producing a Theory of Action, it is crucial to differentiate between the settings in which change will happen (the Theory of Action) from the change mechanisms themselves (the Theory of Change). But both remain inter-related: a Theory of Change and a Theory of Action are intertwined parts of the same logic.

Similarly to a Theory of Change, a Theory of Action has its own logic, processes and mechanisms. It also creates outcomes and impacts of its own.

When a specific delivery model is chosen for a program, it produces certain structures, linkages or partnerships which can have sustained effects in the long term. These can range across:

- Memorandums of understanding, new partnerships created;

- Strength/ maturity of new networks;

- Resources and contributions leveraged from stakeholders;

- Relationships formed with supporting organisations/ government departments as a result of advocacy activities;

- New market linkages created or facilitated; etc.

These are outputs, outcomes and impacts in their own right, which serve as a supporting structure for the Theory of Change to unfold and realise its benefits.

Let’s use the example of the program aiming to increase collaboration between the UK higher education sector and universities, policy institutes and research agencies. The implementation theory focuses on establishing partnerships, which are the basis for the program to delivery its activities (delivering grants, creating research hubs, commissioning joint research programs across countries and institutions).

Despite being a ‘mean to an end’, this partnership delivery model produces structures: academic networks are created, memorandums of understanding are signed between institutions, new stakeholders are brought in and match funding is leveraged from them, etc. In turn, these structures and newly established linkages between institutional actors or individual researchers may lead to further collaborations in the future, beyond the activities supported by the program. This is the implementation logic illustrated on the right-hand side of the diagram below.

Why is it important to use a Theory of Action?

A program theory simply does not exist without a Theory of Action articulating how the Theory of Change will be delivered.

It is important to articulate a Theory of Action at the design stage because it has an effect on the Theory of Change and its delivery. A program theory simply does not ‘exist’ without a Theory of Action, and its rationale cannot be tested unless the program logic specifies how the ‘change logic’ is going to be implemented.

A program’s delivery model creates outputs, outcomes and impacts that should be captured as part of the monitoring and evaluation of the program.

Although results frameworks commonly tend to focus on outputs, outcomes and impacts resulting from the Theory of Change, a program’s delivery model also creates outputs, outcomes and impacts, and there is often an intrinsic value in measuring and monitoring these ‘delivery’ outputs, outcomes and impacts, in particular to capture early signs of sustainability.

It is important to articulate the Theory of Action for a program from an evaluation perspective.

Evaluators often refer to the difference between theory failure and implementation failure, i.e. the difference between a program not working because the Theory of Change is not right (theory failure) and a program not working because the delivery model is dysfunctional or did not unfold the way it should have (implementation failure).

If a Theory of Action is clearly articulated, the evaluator can more easily assess what went wrong – the program’s theory (Theory of Change) or its delivery (Theory of Action).

What next?

To date, Theories of Action have not been used much, either by donors, implementers or evaluators. In cases where an implementation theory is articulated, it is done rather informally and often minimised as a program ‘management plan’. As such, it is hard to tell whether delivery models are fully explored, assessed and reflected upon in the same way that Theories of Change are evidenced, tested, piloted, adapted and made ‘fit for purpose’ to achieve program objectives.

From both the implementation and evaluation perspectives, there is an urgent need to dedicate more attention, time and resources to developing Theories of Action. This will ensure more systematic learning of what works and what does not work in the field of implementation theory and its practice.